CENTERED BODYWORK- STRUCTURAL INTEGRATION, CRANIOSACRAL AND ORTHOPEDIC MASSAGE

|

Sometimes you need a little extra help when you have pain and want to treat yourself at home. Topicals can help safely relieve local pain temporarily, reduce inflammation and even reduce soreness on an area that received a lot of work out or deep massage. Topicals are particularly helpful for muscle strains, arthritis and repetitive stress injuries. Fortunately they also usually have no side effects, unlikely systemic oral pain meds.

Over the years, I have tried many topicals. Here are my favorites. Remember everyone is different so its worth trying a different one if your body and particular issue at this time is not responding to the first topical treatment you try.

0 Comments

Bruce Y. Lee, Forbes

One of my college classmates once decided that to focus on his studies he didn't have time to exercise. So he would sprint everywhere he went at full speed. To the bathroom. To dinner. To class. To the library. To dates (which wasn't often). Would such several-minute bursts be the same as spending dedicated time to regular exercise? Possibly, if you are worried about death, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association. Yes, based on a study conducted by researchers from the National Cancer Institute (Pedro F. Saint‐Maurice, Richard P. Troiano, and Charles E. Matthews) and Duke University (William E. Kraus), the life-extending benefits of physical activity may add up, regardless of whether you do it in one concentrated session or short bursts throughout the day. The study runs over the conventional wisdom (sort of like how my classmate occasionally did to other people) that you've got to get your heart rate up for at least ten minutes for exercise to be of benefit. It also may be another reason to run to the toilet. The study analyzed data from 4,840 adults from the U.S. who were 40 years and older and participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHNES). As part of this survey, the adults wore on their waists for up to a week devices called accelerometers, which could track their movements and thus get a sense of when and how long they were exercising. This way the researchers could figure out how much moderate-to-vigorous physical activity that they were getting each day. The American Heart Association gives the following examples of moderate physical activity:

The researchers used the following measures of the amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity that each adult got each day: total number of minutes, the number of bouts or bursts that were at least 5‐minutes long, and the number of bursts or bouts that were at least 10 minutes long. They also reviewed available death records through 2011. During the follow‐up period of about 6.6 years, 700 deaths had occurred. With all of this information, the researchers could determine whether there was any association between the total amount of physical activity and death and whether this association was different when you only counted bouts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity that was greater than 5 minutes or 10 minutes in duration. Indeed the study did find a correlation between getting more moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and a lower likelihood of death. Compared to people who got little to no regular physical activity, those who got at least 30 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each day were about a third less likely to have died. Those who got 60 to 99 minutes a day were about half as likely to have died. And those who got 100 or more minutes a day were about three-quarters less likely to have died. These correlations seemed to hold regardless of whether the study participants had gotten their physical activity in short bursts throughout the day or in concentrated sessions that were at least 5 or 10 minutes in duration. Of course, remember that this study just shows associations and does not necessarily prove cause-and-effect. Such a study can't show everything that was going on in the study participants' lives. Those who had less physical activity could also have had other behaviors and life circumstances that increased their risk of death such as living in higher crime neighborhoods, working in very stressful or dangerous jobs, having fewer friends and less of a support network, eating less healthy food, having less access to health care, and suffering from poorer health in general. The challenge is that physical activity and these other circumstances form a complex system that then, in turn, affect the likelihood of death. Nonetheless, we already know from many other studies that regular physical activity is good for your health and can help prevent and control numerous potentially life-threatening or life-shortening conditions such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. People have labeled sitting as the new smoking and not the new asparagus. Very few people will say that they need to stop getting so much physical activity and sit on their butts more. However, getting exercise may seem daunting when you have to carve out a block of time each day and go through a series of steps such as traveling to the gym, changing into your tights and "No Guts, No Glory" T-shirt, and doing a repetitive activity (e.g., running on a treadmill) that you wouldn't otherwise do. Even the term "work out" sounds like having an additional job. You don't need a beach or a class to do many exercise movements. (Photo: Shutterstock) Instead, as this study suggests, you could integrate short bursts of physical activity into your regular activities and still get many of the benefits. Here are some examples:

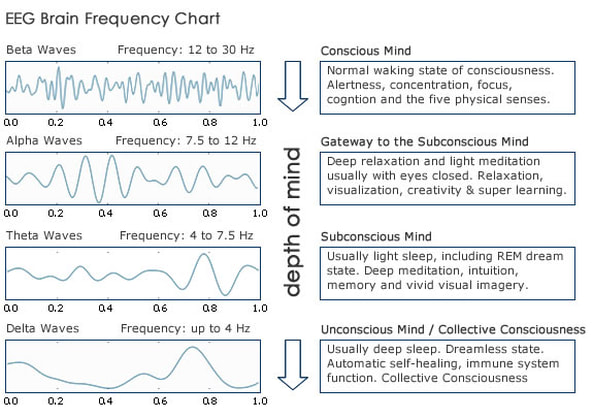

Many clients arrive at my office in a slightly or more than slightly stressed state. This state in brainwave terms is called Beta. Beta allows you to adapt to and function in the modern world. However, when you spend very little time outside of Beta, it can lead to over the long term stress sensitivity, emotional issues, premature aging, illness, insomnia, hormonal imbalance, and increased likelihood of chronic pain. These are your different kinds of brain waves:

Massage is proven in studies to help move you into deeper states of consciousness. How deep depends on where the client is starting from, what type of bodywork, how its delivered, and the consciousness state of the therapist. While it may not be easy to go from Beta to Delta in an hour, even getting to Alpha or some Theta is very healing for the nervous system and the whole body. During waking life, these states are rarer and rarer these days with so much stimulation, demands and fast paced lifestyles. I do relaxation sessions, called Restorative Bodywork, in a very slow and meditative fashion to maximize your time in Theta if possible. The slowness of the massage strokes, acupressure and craniosacral unwinding in particular facilitate more Alpha and Theta, occasionally Delta. I use a calming atmosphere, voice, and theta inducing music to help you go even deeper. How can you get to deeper states of consciousness on your own?

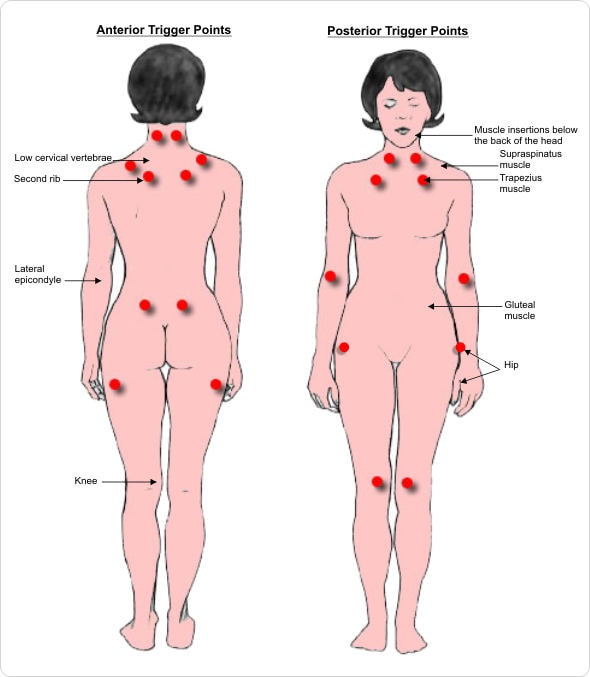

Most of my clients feel significant relief fairly quickly. But as the cases I take on get more and more challenging, a greater portion of these cases have confounding factors that impede recover or even cause the pain directly. It's helpful to explore differential diagnosis if your pain isn't responding to bodywork by a skilled practitioner. If your pain is not improving, it's best to see a doctor, naturopath, or chiropractor and rule out contributing causes. Please do not diagnose and treat yourself based on this or any other article. Here are some common conditions associated with muscle, joint and fascia pain.

Clients who come in for issues besides foot pain, are often unaware of the issues in their feet which may be causing problems up the chain of joints.

Here are some common issues with feet caused by poor shoes: Foot bones that are all glued together, usually in a suboptimal position.

Issues caused by poor shoes and unhealthy feet:

Things to look for in "minimalist" or "barefoot" shoes, unless you already have major issues with your feet that are being addressed by podiatrist:

Consider getting your lower legs, feet and ankles released and realigned to have more functional foundation for your whole body. Two recent studies came out that caught my attention with regards to the importance of mobility. One study came to the conclusion that half of cancers are preventable and lack of exercise/obesity is a major contributor. Another made the connection between mobility and longevity. Those that could easily go from sitting on the floor to standing were living much longer and healthier lives.

These results underscore how much health and life is lost by simply not moving. In a way, when you don't exercise you are making an unconscious decision to live a shorter life with more discomfort and possibly an arduous and expensive journey fighting illnesses like cancer, diabetes and heart disease. So considering making a better relationship with your body your New Year's resolution. Below are some ways to help you be more mobile and healthy in 2018. Pick one first and commit to that. Too many goals will leave you lost at sea. If you need help, check out this article on how to keep your resolution.

From Quartzy

By Rosie Spinks November 9, 2017 Sentences that start with the phrase “A guru once told me…” are, more often than not, eye-roll-inducing. But recently, while resting in malasana, or a deep squat, in an East London yoga class, I was struck by the second half of the instructor’s sentence: “A guru once told me that the problem with the West is they don’t squat.” This is plainly true. In much of the developed world, resting is synonymous with sitting. We sit in desk chairs, eat from dining chairs, commute seated in cars or on trains, and then come home to watch Netflix from comfy couches. With brief respites for walking from one chair to another, or short intervals for frenzied exercise, we spend our days mostly sitting. This devotion to placing our backsides in chairs makes us an outlier, both globally and historically. In the past half century, epidemiologists have been forced to shift how they study movement patterns. In modern times, the sheer amount of sitting we do is a separate problem from the amount of exercise we get. Our failure to squat has biomechanical and physiological implications, but it also points to something bigger. In a world where we spend so much time in our heads, in the cloud, on our phones, the absence of squatting leaves us bereft of the grounding force that the posture has provided since our hominid ancestors first got up off the floor. In other words: If what we want is to be well, it might be time for us to get low. To be clear, squatting isn’t just an artifact of our evolutionary history. A large swath of the planet’s population still does it on a daily basis, whether to rest, to pray, to cook, to share a meal, or to use the toilet. (Squat-style toilets are the norm in Asia, and pit latrines in rural areas all over the world require squatting.) As they learn to walk, toddlers from New Jersey to Papua New Guinea squat—and stand up from a squat—with grace and ease. In countries where hospitals are not widespread, squatting is also a position associated with that most fundamental part of life: birth. It’s not specifically the West that no longer squats; it’s the rich and middle classes all over the world. My Quartz colleague, Akshat Rathi, originally from India, remarked that the guru’s observation would be “as true among the rich in Indian cities as it is in the West.” But in Western countries, entire populations—rich and poor—have abandoned the posture. On the whole, squatting is seen as an undignified and uncomfortable posture—one we avoid entirely. At best, we might undertake it during Crossfit, pilates or while lifting at the gym, but only partially and often with weights (a repetitive maneuver that’s hard to imagine being useful 2.5 million years ago). This ignores the fact that deep squatting as a form of active rest is built in to both our evolutionary and developmental past: It’s not that you can’t comfortably sit in a deep squat, it’s just that you’ve forgotten how. “The game started with squatting,” says author and osteopath Phillip Beach. Beach is known for pioneering the idea of “archetypal postures.” These positions—which, in addition to a deep passive squat with the feet flat on the floor, include sitting cross legged and kneeling on one’s knees and heels—are not just good for us, but “deeply embedded into the way our bodies are built.” “You really don’t understand human bodies until you realize how important these postures are,” Beach, who is based in Wellington, New Zealand, tells me. “Here in New Zealand, it’s cold and wet and muddy. Without modern trousers, I wouldn’t want to put my backside in the cold wet mud, so [in absence of a chair] I would spend a lot of time squatting. The same thing with going to the toilet. The whole way your physiology is built is around these postures.” In much of the world, squatting is as normal a part of life as sitting in a chair.So why is squatting so good for us? And why did so many of us stop doing it? It comes down to a simple matter of “use it or lose it,” says Dr. Bahram Jam, a physical therapist and founder of the Advanced Physical Therapy Education Institute (APTEI) in Ontario, Canada. “Every joint in our body has synovial fluid in it. This is the oil in our body that provides nutrition to the cartilage,” Jam says. “Two things are required to produce that fluid: movement and compression. So if a joint doesn’t go through its full range—if the hips and knees never go past 90 degrees—the body says ‘I’m not being used’ and starts to degenerate and stops the production of synovial fluid.” A healthy musculoskeletal system doesn’t just make us feel lithe and juicy, it also has implications for our wider health. A 2014 study in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology found that test subjects who showed difficulty getting up off the floor without support of hands, or an elbow, or leg (what’s called the “sitting-rising test”) resulted in a three-year-shorter life expectancy than subjects who got up with ease. In the West, the reason people stopped squatting regularly has a lot to do with our toilet design. Holes in the ground, outhouses and chamber pots all required the squat position, and studies show that greater hip flexion in this pose is correlated with less strain when relieving oneself. Seated toilets are by no means a British invention—the first simple toilets date back to Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium B.C., while the ancient Minoans on the island of Crete are said to have first pioneered the flush—but they were first adopted in Britain by the Tudors, who enlisted “grooms of the stool” to help them relieve themselves in ornate, throne-like loos in the 16th century. The next couple hundred years saw slow, uneven toilet innovation, but in 1775 a watchmaker named Alexander Cummings developed an S-shape pipe which sat below a raised cistern, a crucial development. It wasn’t until after the mid-to-late-1800s, when London finally built a functioning sewer system after persistent cholera outbreaks and the horrific-sounding “great stink” of 1858, that fully flushable, seated toilets started to commonly appear in people’s homes. Today, the flushable squat-style toilets found across Asia are, of course, no less sanitary than Western counterparts. But Jam says Europe’s shift to the seated throne design robbed most Westerners of the need (and therefore the daily practice) of squatting. Indeed the realization that squatting leads to better bowel movements has fueled the cult-like popularity of the Lillipad and the Squatty Potty, raised platforms that turn a Western-style toilet into a squatting one—and allow the user to sit in a flexed position that mimics a squat. “The reason squatting is so uncomfortable because we don’t do it,” Jam says. “But if you go to the restroom once or twice a day for a bowel movement and five times a day for bladder function, that’s five or six times a day you’ve squatted.” While this physical discomfort may be the main reason we don’t squat more, the West’s aversion to the squat is cultural, too. While squatting or sitting cross legged in an office chair would be great for the hip joint, the modern worker’s wardrobe—not to mention formal office etiquette—generally makes this kind of posture unfeasible. The only time we might expect a Western leader or elected official to hover close to the ground is for a photo-op with cute kindergarteners. Indeed, the people we see squatting on the sidewalk in a city like New York or London tend to be the types of people we blow past in self-important rush. “It’s considered primitive and of low social status to squat somewhere,” says Jam. “When we think of squatting we think of a peasant in India, or an African village tribesman, or an unhygienic city floor. We think we’ve evolved past that—but really we’ve devolved away from it.” Avni Trivedi, a doula and osteopath based in London (disclosure: I have visited her in the past for my own sitting-induced aches) says the same is true of squatting as a birthing position, which is still prominent in many developing parts of the world and is increasingly advocated by holistic birthing movements in the West. “In a squatting birthing position, the muscles relax and you’re allowing the sacrum to have free movement so the baby can push down, with gravity playing a role too,” Trivedi says. “But the perception that this position was primitive is why women went from this active position to being on the bed, where they are less embodied and have less agency in the birthing process.” Children in the West squat with ease. Why can’t their parents?So should we replace sitting with squatting and say goodbye to our office chairs forever? Beach points out that “any posture held for too long causes problems” and there are studies to suggest that populations that spend excessive time in a deep squat (hours per day), do have a higher incidence of knee and osteoarthritis issues. But for those of us who have largely abandoned squatting, Beach says, “you can’t really overdo this stuff.” Beyond this kind of movement improving our joint health and flexibility, Trivedi points out that a growing interest in yoga worldwide is perhaps in part a recognition that “being on the ground helps you physically be grounded in yourself”—something that’s largely missing from our screen-dominated, hyper-intellectualized lives. Beach agrees that this is not a trend, but an evolutionary impulse. Modern wellness movements are starting to acknowledge that “floor life” is key. He argues that the physical act of grounding ourselves has been nothing short of instrumental to our species’ becoming. In a sense, squatting is where humans—every single one of us—came from, so it behooves us to revisit it as often as we can. Read the full article by Dr. Axe here.

Here's the article summary: "Bulging Disc Takeaways"

From James Hamblin at the Atlantic:

Elite tennis players have an uncanny ability to clear their heads after making errors. They constantly move on and start fresh for the next point. They can’t afford to dwell on mistakes. Peter Strick is not a professional tennis player. He’s a distinguished professor and chair of the department of neurobiology at the University of Pittsburgh Brain Institute. He’s the sort of person to dwell on mistakes, however small. “My kids would tell me, dad, you ought to take up pilates. Do some yoga,” he said. “But I’d say, as far as I’m concerned, there's no scientific evidence that this is going to help me.” Still, the meticulous skeptic espoused more of a tennis approach to dealing with stressful situations: Just teach yourself to move on. Of course there is evidence that ties practicing yoga to good health, but not the sort that convinced Strick. Studies show correlations between the two, but he needed a physiological mechanism to explain the relationship. Vague conjecture that yoga “decreases stress” wasn’t sufficient. How? Simply by distracting the mind? The stress response in humans is facilitated by the adrenal glands, which sit on top of our kidneys and spit adrenaline into our blood whenever we’re in need of fight or flight. That stress response is crucial in dire circumstances. But little of modern life truly requires it (especially among academic scientists). Most of the time, our stress responses are operating as a sort of background hum, keeping us on edge. Turn that off, and we relax. “It might explain why certain sensations we find very relaxing or stressful.”For a long time, it has been understood that the adrenal glands were turned on and off by a couple discrete pathways coming from the brain. “Folks said there was one particular cortical area, perhaps two, that controlled the adrenal medulla,” Strick explained. Randy Bruno, an associate professor of neuroscience at Columbia University, further explained that “the way people usually think about the cortex, it’s very hierarchical.” That is, perceptions come in from the world and get sent from one part of the brain to the next, to the next, to the next. They go all the way up the chain of command to the frontal cortex. That sends some signals down to create motor actions. If stress is controlled by these few cortical areas—the part of the brain that deals in high-level executive functioning, our beliefs and existential understandings of ourselves—why would any sort of body movement play a part in decreasing stress? Now Strick seems to have solved his own problem. In the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the Pittsburgh neuroscientists showed that they have discovered a discrete, elaborate network in the cerebral cortex that controls the adrenal medulla. It seems that the connections between the brain and the adrenal medulla are much more elaborate than previously understood. Complex networks throughout the primary sensory and motor cortices are tied directly to our stress responses. That discovery transformed Stricks’ understanding of how bodily movements influence our health. He’s starting pilates. “This is suggesting a much more decentralized process,” said Bruno of the findings. He was not involved in the study.“You have lots of different circuits built on top of one another, and they’re all feeding back to one of our most primitive and primordial response systems. They've really shown that stress is controlled by more than the traditional high-level cognitive areas. I think that’s a big deal.” To explain the implications of this new brain-adrenal “connectome”—as new neural connections are often now being called—requires a look at the mapping process. Rabies can be a fantastic tool, in the right hands. Inject it into an organ, and the nerves that feed that organ will take the virus up and carry it backward toward the central nervous system. En route, the virus hijacks the machinery of the nerves in the cell body and dendrites to replicate and grow its numbers, then cross the synapse from a neuron backwards into all of its inputs. By charting the progress of the virus, scientists can map out the neural connections between an organ and the brain in ways that were previously impossible. In this case, Strick and his team injected the adrenal glands of monkeys. “How we move, think, and feel have an impact on the stress response through real neural connections.”Rabies moves at a predictable rate, replicating every eight to 10 hours, moving rapidly through chains of neurons and revealing a network. The researchers could allow the virus to move up the nervous system and reach the brain but could sacrifice the monkey before it showed any symptoms of infection. “If someone dies of a herpes infection, their temporal lobes look like soup,” Strick explained to me. He contrasted that with the brain of someone who dies of a rabies infection, which looks grossly normal. It’s still an open question how exactly rabies disables our nerves. It can live inside a neuron for a while innocuously—which allows rabies to move through a population. So, Strick emphasizes, the monkeys weren't suffering. When the virus has had enough time to travel a predictable distance, the researchers anesthetize the animal, wash out its blood, perfuse the central nervous system with fixatives, and use antibodies to detect where the virus has spread. The kills were timed to various stages to create a map. By the time you’ve gone through several sets of synapses that mapping is an enormous task. There’s an exponential increase in the number of neurons. Once they managed to chart the connections, though, the researchers were astounded at what they saw. The motor areas in the brain connect to the adrenal glands. In the primary motor cortex of the brain, there’s a map of the human body—areas that correspond to the face, arm, and leg area, as well as a region that controls the axial body muscles (known to many people now as “the core”). The Pitt team didn't think the primary motor cortex would control the adrenal medulla at all. But there are a whole lot of neurons there that do. And when you look at where those neurons are located, most are in the axial muscle part of that cortex. “Something about axial control has an impact on stress responses,” Strick reasons. “There’s all this evidence that core strengthening has an impact on stress. And when you see somebody that's depressed or stressed out, you notice changes in their posture. When you stand up straight, it has an effect on how you project yourself and how you feel. Well, lo and behold, core muscles have an impact on stress. And I suspect that if you activate core muscles inappropriately with poor posture, that’s going to have an impact on stress.” “These neural pathways might explain our intuitive sense for why there are many different strategies for coping with stress,” said Bruno. “I like the examples they give in the paper—that maybe this is why yoga and pilates are so successful. But there are lots of other things where people talk about mental imagery and all sorts of other ways that people deal with stress. I think having so many neural pathways having direct lines to the stress control system, that’s really interesting.” Strick focused on movement, but Bruno specializes in sensory neuroscience, so he read more into the findings in the primary somatosensory cortex. Some of these tactile areas in the brain seem to be providing as much input to the adrenal medulla as the cortical areas. “To me that's really new and interesting,” said Bruno. “It might explain why certain sensations we find very relaxing or stressful.” I thought of a good back scratch, or, for some reason, the calming sensation of putting your bare hand into a plate of fresh pasta. The idea that primary sensory and motor areas in the brain have a part in to modifying internal states in such a prominent way has caused Bruno to question the very nature of these areas of the brain. “It's not clear to me—from our work, and from their work—that what we call motor cortex is really motor cortex,” he said. “Maybe the primary sensory cortex is doing something more than we thought. When I see results like these, I go, hm, maybe these areas aren’t so simple.” With this come implications for what’s currently known as “psychosomatic illness”—how the mind has an impact over organ functions. The name tends to have a bad connotation. The notion that this mind-body connection isn’t really real; that psychosomatic illnesses are “all in your head.” Elaborate connections like this would explain that, yes, it is all in your head. The fact that cortical areas in the brain that have multi-synaptic connections that control organ function could strip the negative connotations. The Pitt team has previously injected the heart and seen cortical areas that are involved in controlling its rhythm. They believe that may explain cases of sudden unexpected death—from epilepsy, from brain injury, even from strong emotional stimuli (positive and negative) leading to heart attacks. There is also the emerging field of neuro-immunology, which is looking at the effects of stress on the immune system. All of this lends some credence to people who may once have been dismissed by people like Strick himself, who are skeptical of anything that isn’t borne out by a concrete mechanism. As he put it, “How we move, think, and feel have an impact on the stress response through real neural connections.”

I first studied various forms of Asian bodywork at the Acupressure Institute in Berkeley. A core part of our training was Tai Chi/Qi Gong exercises, which were developed in China over thousands of years as medical treatment. After studying and practicing different forms of exercise, I believe Qi Gong offers the most well rounded exercise and is particularly helpful for those who are injured or ill. The purpose according to Traditional Chinese Medicine is to build your Qi or energy and unblock blockages of meridian flows that include acupuncture and acupressure points. I frequently recommend my clients take up Qi Gong as an adjunct therapy.

From a Western perspective, Qi Gong can have the following effects:

In honor of my beloved master teacher, Brian O'Dea, I posted his instruction of some forms of Qi Gong/Tai Chi exercises if you would like to practice at home. I am happy to say Brian is alive and well, practicing and teaching in Berkeley, CA. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed